Retirement Planning: A First Look at Accumulation and Distribution of Wealth

Preface: Retirement planning is not something that can be feasibly fleshed out in one 2,500-word memo, therefore consider this part one of a multi-part series on retirement (the number of parts to be determined at a later date). In Book X of the Odyssey, the wind god Aiolos gave Odysseus a bag of wind, to use sparingly as he and his crew sailed home to Ithaca. With Odysseus dispensing small breaths of wind from the bag, ten days passed and the crew neared home. Ithaca was clearly in sight, but the job was not quite finished. Quoting Homer:

“now on our tenth [day] our native land came in sight, and lo, we were so near that we saw men tending the beacon fires…”

Upon seeing land, Odysseus succumbed to sleep, having spent the last nine nights guarding the priceless bag of west-blowing wind. The crew became suspicious of Odysseus’ defensive behavior. Why is Odysseus guarding that bag with such intense protection? Perhaps it is a treasure the captain actively hides from us? Quoting Homer:

“Much goodly treasure is [Odysseus] carrying… while we, who have accomplished the same journey as he, are returning, bearing with us empty hands… Nay come let us quickly see what is here, what store of gold and silver is in the wallet.”

Homer makes it clear that the crew felt entitled to whatever reward Odysseus had received, particularly because of the tribulations they had to endure. Sadly, for both the crew and the slumbering Odysseus, there was neither gold nor silver in that bag. As they loosened the strings of the bag, a huge tornado of wind seized their ship and transported them back to the island of Aiolos. In the crew’s effort to share in the splendors of plunder, they added 14 additional chapters to the Odyssey and all of the dangers that came with it.

The bag of wind acts as a metaphor and is still apropos today. I can have a perfectly good asset allocation, suitable to my needs and risk tolerance and be tempted to see what’s inside the bag of wind. Here the bag is a hot stock tip, the latest and “greatest” IPO, a “once in a lifetime” private venture, or maybe even a lottery ticket. Just because there is a possibility of winning or making a big score doesn’t make it probable or a good investment. When it comes to our finances, impulsivity can get in the way of our long term goals. If we don’t want to miss out on the plunders of war, don’t open the bag of wind. Instead, focus on having a long term diversified asset allocation. It’s not sexy like a mysterious bag of “gold”, but it will get the job done over the long term.

Furthermore, if we haven’t stepped foot on the shores of Ithaca, there is no time for napping. We need to finish the task or a goal, whether it be saving for our children’s college, planning for retirement, laying aside funds for a new home or any other goal we may have. The task is not done until all the money is in the bank. I’m not prescribing self-imposed insomnia. Instead, plan ahead, chip away at your goals and most importantly do not give up (or open the bag of wind, it may blow all your money away).

Now onto crunching numbers! How much do you need for retirement?

You can ascertain this number in a couple of ways:

The “hard” way, aka financial planning number crunching: determine your income replacement rate (ie the amount your need your portfolio to generate annually to replace your foregone compensation after retirement), estimate an inflation rate, estimate a return on investment your portfolio will achieve, calculate the amount you will need to retire.

Or the “easy” way, aka lazy man’s multiplication: take your annual spending and multiply it by somewhere between 20 and 50. Let’s assume you spend $150,000 per year. The table below shows how much you will need to retire if you were to choose anywhere between a 2% and a 5% withdrawal rate, provided you were to continue spending $150,000 per year.

Table 1.

*a note on the hard way: while this may be considered more precise, estimates are still involved regarding rates of return and inflation

*a note on the easy way: this does not factor in inflation, but does give you a rough idea of what you will need to retire and maintain your standard of living

* a note on the red box: the 4% withdrawal rate is known as the “sustainable withdrawal rate” which I will discuss further later in this article.

In the end, what does this really boil down to? Your ability to retire is in large part dependent on your savings rate as a percentage of your take-home pay. To further break this down, how much you have and when you retire depends on how much you take home each year, balanced with how much you live on.

Looking at an example of savings, if we hold a 50%/50% stock bond portfolio with an average annual rate of return of 7%, according to the rule of 72, we would double our money in a little over 10 years. If we saved a percentage of pay on an annual basis, each annual contribution would take 10 years to double on a rolling basis. Here’s what each of the returns in dollar amounts would look like on saving 5%, 10%, 20%, 25% and 30% of a take home pay of $150,000:

Table 2.

Referencing the table above, my savings rate drastically changes the amount of money available to me in retirement. By saving five times more money each year, miraculously I end up with five times more in retirement. You’re probably thinking “Duh! Of course saving 5x more means 5x more money for retirement”. The bottom line is, my savings rate dictates when I can retire. If I have only saved $329,000 by the time I am 50, (I am nearly 30 today), it will be hard for me to justify retiring. I would have to figure out how to live on approximately $13,200 per year to maintain the sustainable withdrawal rate of 4% (Math: $329k * 0.04). If I have saved $1.9 million by age 50, I will have nearly $80,000 (pretax) to live on in retirement, without touching my principal investment.

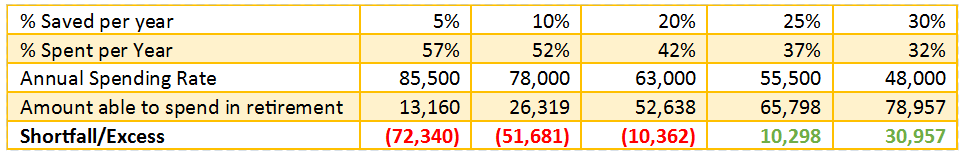

The neat thing about the savings rate is that it is inversely correlated to the spending rate. For instance, if I save 30% of my take-home pay, I am likely only spending around 30-35% (once we factor in taxes and social security). If I only save 5%, I am spending closer to 55-60% of my take-home pay. By saving more, not only am I increasing my savings for retirement at a much more rapid rate, but I am also reducing the amount I would theoretically need to live on in retirement. The following chart show’s estimated spending rates and dollar amounts using the same $150,000 take home pay and year 20 estimated retirement amounts from Table 2:

Table 3.

Ironically, if I spent $85,500 per year, I would need to save more than 30% of my income to have enough of money in retirement to support my spending. If I only spent $48,000, I would be accumulating principal in retirement. The chart above also shows us that the ideal savings rate is somewhere between 20 and 25%. It also shows that my spending rate significantly affects the year I can retire.

This brings us to our withdrawal rate. In order to properly calculate our retirement fund, we must know how much we will be taking out (on average) on an annual basis. There are a number of factors ultimately determining your decision:

- What is your risk tolerance?

- “Lower-Risk-You” will withdraw a lower portion of your portfolio, closer to the 3% range, due to concerns of outliving your money

- “Higher-Risk-You” will do the opposite; this doesn’t concern you and you are likely allocated more aggressively, even in retirement

- What are the things you cannot live without, despite no longer being in the workforce?

- Unwillingness to change lifestyle without employment will lead to more withdrawals to pay bills

- Willingness to live on the lower end of living standards will lead to less withdrawals

- Do you have heirs or a charity you wish to leave funds to?

- If you would like your children, loved ones or even a charity to receive an inheritance, you should withdraw less from your portfolio

- If you don’t, you can increase your withdrawal rate

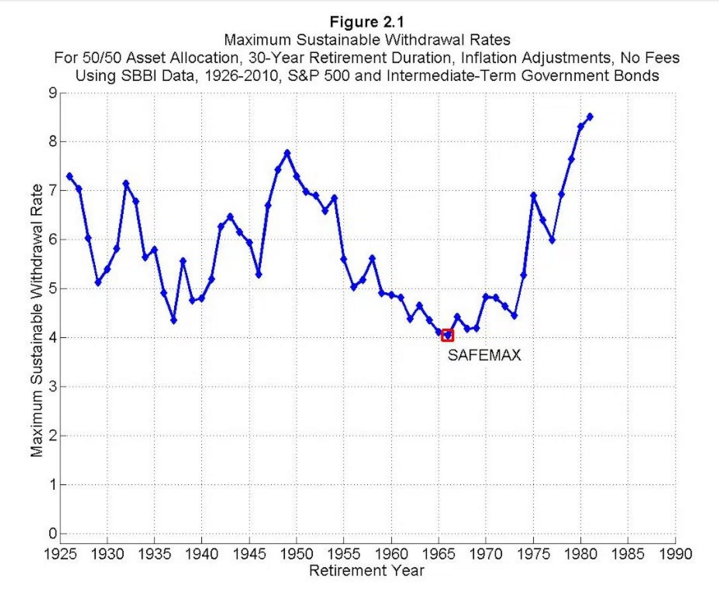

So what is the “Safe Withdrawal Rate”? A classic study on retirement planning is known as the Trinity Study. It discusses how to choose an appropriate withdrawal rate that is sustainable. I can write an entire memo discussing the nitty gritty details of the study, so for now let’s look at the basic premise and what it means for those of us planning for retirement or those of us who are already retired.

The Trinity study is an analysis of what would have happened for a hypothetical person who spent 30 years in retirement over rolling periods. They started with 1925 – 1955, then 1926 – 1956, 1927 – 1957, 1928 – 1958, and so on. This person held a 50% stock 50% bond (comprised long term high grade corporate bonds) portfolio. Then they forced the hypothetical retiree to spend increasing percentages of their portfolio each year, indexed to inflation as defined by the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The study defines a success as not losing one’s shirt over a given 30-year period.

The conclusion of the study is that a conservative 3-4% withdrawal rate has the greatest chance of being a success. 5% withdrawal can work over shorter retirement periods or with a more aggressively positioned portfolio. Anything above 5% has significantly lower success rates. The study also showed that retirees need to maintain at least a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio to achieve success. More conservative portfolios require either shorter retirement periods or lower withdrawal rates.

Note this study assumes the retiree will:

- not earn any additional money through part time work or other side ventures

- not collect anything from Social Security (depending on your age, this one is relevant)

- not adjust spending due to an economic reality like a recession (most people do not react this way, unless they truly have a good cushion)

- not substitute goods due to spikes in inflation (ie switch from fish to meat or vice versa depending on the price)

- not collect any inheritance from passing loved ones

- not spend less with age (many studies suggest people do tend to spend less as they get older)

What I take away from this is: 4% is the number to keep in mind. This is because I would rather have a margin of safety than worry for the last few years of my life about whether or not I will be penniless. My goal isn’t to die with $0.01 in my bank account and I presume yours isn’t either. In fact, I would like to leave much more than that to my family. Retirement planning and our mortality is something we must contemplate. It can be scary to think about, but with the right plan, ample savings and a conservative withdrawal rate in retirement, you’ll be well prepared.

Notes and Sources:

The “rule of 72” is a simplified way to look at how long it will take for your assets to grow. 72 divided by your annual rate of return is the number of years required to double your investment. For example, if your rate of return is 8%, your assets will take 9 years to double (72 ÷ 8). Let’s say you are planning to retire in 36 years from now (making the numbers round). If you start investing for your future today, your money will have 4 cycles to double (36 ÷ 9). A simple investment of $10,000 today will be $80,000 in 36 years, 8x the amount of money. This is why planning for retirement early is so important. The sooner you begin to save, the longer amount of time you will have to let your assets grow.

Wade Pfau, PhD, CFA, “The Trinity Study and Portfolio Success Rates” http://retirementresearcher.com/the-trinity-study-and-portfolio-success-rates/

SAFEMAX chart credit to Wade Pfau

Disclosures: This bulletin expresses the views of the author as the date indicated and such views are subject to change without notice. This communication is intended to be distributed to current clients and certain interested parties only. This communication should not be construed as an advertisement offering our firm's investment advisory services. This communication is not a solicitation or recommendation of any particular investment strategy.