Currency and Volatility

“Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.” -Warren Buffett

The third quarter certainly showed much to fear, with China and Syria topping the list. Market participants sold risk assets in anticipation of poor growth out of both China and multinational corporations’ China strategy. Both the Chinese economy and the American economy are essential to global growth. The Chinese economy is not falling off a cliff, instead its growth is merely slowing down, much like our own growth rate, which has slowed over the past 20 years. As the pool of capital becomes larger and the demographics change, high levels of growth become increasingly difficult to sustain. To not repeat last month’s China commentary, this quarter I will put China’s currency manipulation into perspective. I will also discuss the resulting volatility in global markets and how we should approach it.

Since the late 1970s, there has been a codependency between the US and China. America experienced straining stagflation and the Chinese economy suffered following its Cultural Revolution. China provided cheap goods enabling income-constrained Americans to make ends meet. The US provided the external demand aiding China’s export-led growth strategy.

Over the years this relationship intensified. The US relied on China’s surplus in savings to close the widening budget deficit. As China has run a huge trade surplus with the US since 1985, China has been steadily accumulating US dollars and US Treasury securities for decades.

China’s Reasons and Process for Buying US Treasuries

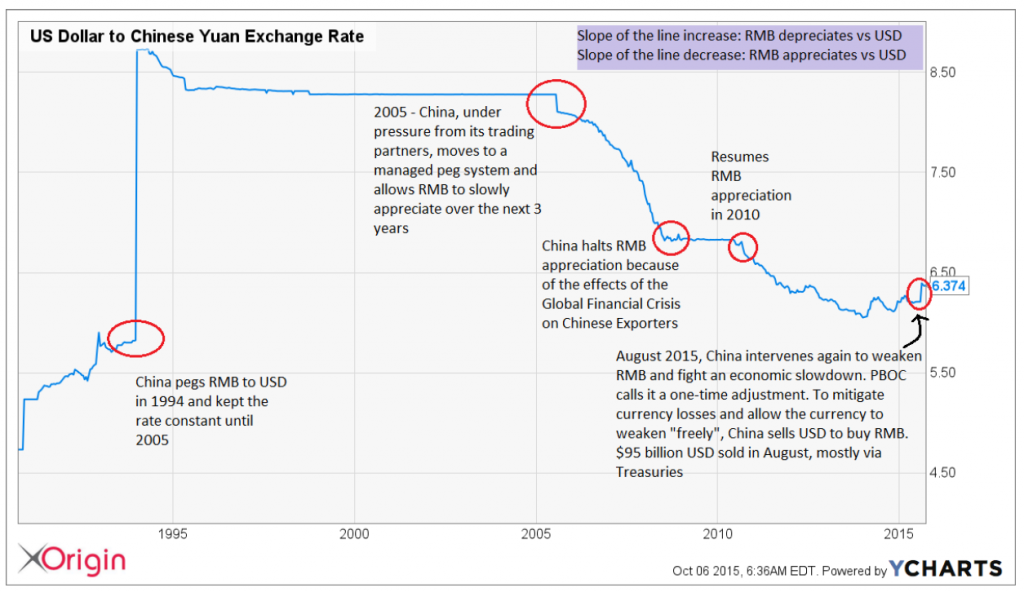

You can see that the PBOC’s policies and procedures surrounding currency intervention are not as clear cut as the United States has been claiming. For example, in November of 2011, President Obama stated that China needed to “go ahead and move towards a market-based system for their currency”. By this time, China had already allowed their currency to appreciate versus the dollar (see chart below referencing 2010 for the timeline). The US notoriously reprimands China for currency manipulation on the grounds that RMB is undervalued relative to the dollar, causing US exports to be much less competitive in price than China’s. The US also blames an undervalued RMB for causing the huge trade deficit (now at $364 billion on a trailing twelve month basis). Meanwhile at home, America fails to address its core economic problems that result from a lack of domestic savings. The net national savings rate stood at 2.9% as of mid-2015, compared to 6.3% on average from 1970-2000. It is clear: China’s vast reservoir of surplus savings helps fund record budget deficits.

While the PBOC’s level of intervention may be excessive, China has not been the only country to manipulate their currency or peg their rate to another reserve currency. Some examples: in 2011, the Swiss pegged their currency to the euro, following a series of other moves in 2010 to prevent their currency from appreciating too much during the global financial crisis, from 2008 – 2014 the US weakened the dollar through QEs 1, 2 and 3, lastly in 2012 Shinzo Abe began “Abenomics” that included manipulating the Japanese yen. Additionally, China’s intervention has had some economic rationality. As a net exporter, and invariably a net lender to the United States, China has liabilities in RMB (from manufacturing goods and needing to pay for equipment and labor), while they have assets in USD and other major currencies (from collecting payment for goods and services abroad). At some point, there needs to be a conversion of RMB to USD and vice versa to make their global exchange work. RMB is relatively illiquid compared to USD and thus the PBOC intervention helped stabilize the market.

The chart above shows the exchange rate between RMB and USD. From July of 2005 to June of 2013, RMB appreciated by 34% on a nominal basis and by 42% on an inflation-adjusted (real) basis. During this time, the Chinese government continued to accumulate US Treasuries and USD foreign reserves as it allowed RMB to slowly appreciate over time. Notably, prior to the government’s intervention in August of this year, China’s current account surplus had declined (meaning, China is exporting less than before) and its gathering of foreign exchange reserves had slowed (because PBOC has not needed to intervene as often to manage its currency). This suggests a couple of factors:

- The Chinese currency might not be as undervalued against the dollar as it once was (i.e. before 2005, and before PBOC intervened to strengthen the currency, as directed by its trading partners, mainly the United States). Allowing RMB to weaken would strengthen China’s competitive ability to export goods and services in the global economy. However, this assumes a portion of their exports were hindered by an appreciating RMB and not by other factors.

- China’s current account surplus may be on the decline because its economy is becoming more consumption-oriented domestically, rather than export-oriented globally. If this is the case, a weaker RMB directly hinders Chinese ability to bid for goods and services both at home and abroad.

The two factors above have a number of implications for both America and China. The Chinese government has established it will do anything to stimulate growth. In the past, China has produced growth through exports and infrastructure investment. The government is familiar with this route and has taken steps to weaken its currency to stimulate growth, even to the detriment of its citizens purchasing goods and services. Additionally, the US has pressed China to lean its growth more toward private consumption rather than exports. Nevertheless, a weaker RMB will make it difficult for China to maintain high levels of growth from a consumption economy.

It’s also unclear how a change in the Chinese economy would affect US interest rates. If China shifts toward a consumption model, household savings could decline. China would no longer supplement the savings of Americans. A consumption boom in China also means fewer exports to America, which could create American jobs—though the US can just import from other low-cost providers. In this scenario, a decline in exports to America means the PBOC would not intervene as often to buy dollars and sell RMB to manufacturers. Without this intervention, China would buy fewer US Treasuries and interest rates could rise.

As China transitions into a consumption model, savings rates don’t necessarily need to decline. If the growth continues in China and its citizens spend proportionally the same amount, savings rates should remain the same. China can continue to purchase Treasuries and rates are unaffected. Conversely if growth and savings rates decline, China is likely to sell US Treasuries. One might think this would affect US interest rates, however, despite the PBOC’s sales, US interest rates declined through August and September. This is because the decline in manufacturing in China caused fear in the market, thereby creating a “risk-off” scenario where there were large buyers of US Treasuries offsetting the sales from the PBOC. Ultimately, I think the Fed has more control over (at least) the short end of the yield curve and in light of no inflation, a strong dollar, and poor growth coming from China, Yellen is unlikely to increase rates this year.

Arguably, the US is in a better position than China with regards to manufacturing. America has outsourced cheap labor for so long that there is comparably less manufacturing infrastructure in place. Having said that, the US is in a unique position to build new factories with a technological advantage. For instance, GE has developed software called Predix. This software is currently being used by Pitney Bowes, and it delivers and analyzes data from machines to provide client and productivity services, as well as automation capabilities. Clearly, the United States is innovative and will continue to modernize and update business operations and processes. In Africa, the population never used landlines because cell phones were invented before the necessary landline infrastructure was built. There are advantages to joining later, as capabilities increase and archaic machines are not there to deter technological capital expenditures. The US can build with increased technology, because sometimes it is easier to build from scratch than to remodel the existing equipment. China has long used cheap labor to their advantage and thus has not needed automation to improve manufacturing outputs. Conversely, the US does not have cheap labor here; instead America can automate processes and use technology to produce low cost items.

The prospects of China may seem bleak and there is much uncertainty. On the bright side, this may bring about a boom in American manufacturing, which would ameliorate GDP growth at home. It may also force China to turn to technology as their middle class grows and cheap labor becomes less available.

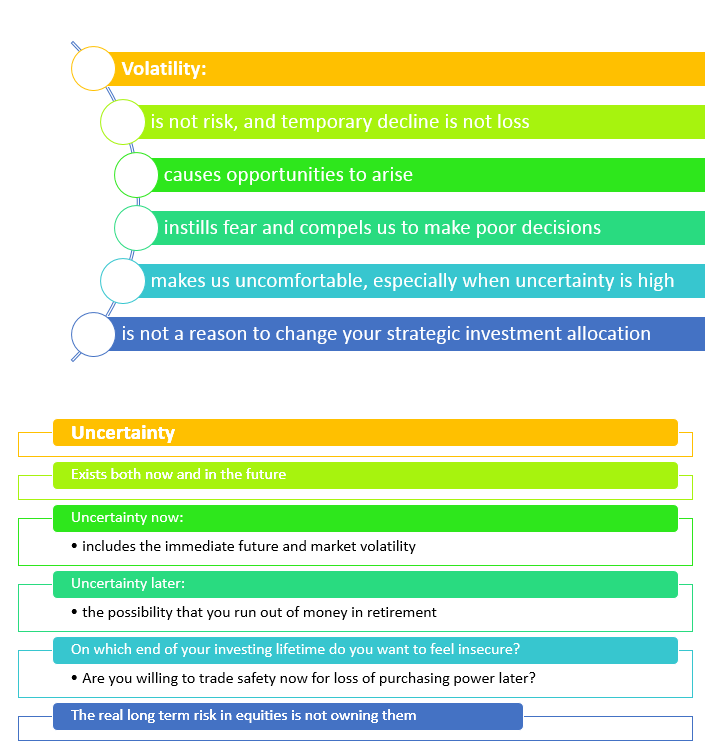

All of this brings me to my next point: volatility. There are uncertainties in the market causing participants to sell equities and buy treasury bonds (“risk-off”). The future outlook for China is unknown. We don’t know when Janet Yellen will raise interest rates. There are growing tensions between the United States and Russia. Terrorist attacks have been abundant in Europe and Africa. There will always be risk, whether it be known or unknown in the market because no one knows the future. We don’t know what will be, but we can control how we react to it.

All of this brings me to my next point: volatility. There are uncertainties in the market causing participants to sell equities and buy treasury bonds (“risk-off”). The future outlook for China is unknown. We don’t know when Janet Yellen will raise interest rates. There are growing tensions between the United States and Russia. Terrorist attacks have been abundant in Europe and Africa. There will always be risk, whether it be known or unknown in the market because no one knows the future. We don’t know what will be, but we can control how we react to it.

The last quarter reminds us that markets don’t go straight up. There hasn’t been more than one month’s worth of volatility since 2011. It’s easy to forget the fear and pain the financial crisis of 2008 caused. Know that these emotions are temporary. Accept how you feel and continue to stay the course. As always, I am here to answer any questions you may have. Please feel free to reach out.

Sources:

Recent news: http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-27/china-said-to-sell-treasuries-as-dollars-needed-for-yuan-support

Morrison & Labonte. 2013, “China’s Currency Policy: An Analysis of Economic Issues”

China Statistics: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ch.html

Net National Savings Rates: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.ADJ.NNAT.GN.ZS

Ycharts for USD/CNY pricing

Duration and yield calculations from TD Ameritrade Data and Schwab PortfolioCenter Outputs

Disclosures

This bulletin expresses the views of the author as the date indicated and such views are subject to change without notice. It is important to understand investing in general involves risk of loss that you should be prepared to bear. Please refer to our Firm’s Form ADV Part 2 Disclosure Brochure for more information regarding the risks of the investments held in your account. Our calculated perceived value is an opinion based on the information we have at the time of our forecast. The risk assumed is that the market will fail to reach expectations of perceived value. Our opinions, forecasts or predictions of future events, returns or results are subject to change and are not guarantees of future events, returns or results. This communication is intended to be distributed to current clients and certain interested parties only. This communication should not be construed as an advertisement offering our firm's investment advisory services.